Amid severe power shortages and rising global energy insecurity, Japan and India, Asia’s second- and third-largest economies, are in a race to meet ambitious 2030 climate goals. Getting there will require enormous new spending—a prospect that is far from guaranteed.

As the world’s largest energy consumer, China gets most of the climate-policy attention in Asia. But Japan and India will need to make major changes to keep climate change in check, too. Both nations have set ambitious goals. But significant new threats loom large.

In India, a country that has long struggled to mobilize infrastructure investment, rising global interest rates could derail lofty clean-power plans. In Japan, a recent electricity-pricing policy change may make financing green power plants more difficult. And both nations continue to struggle with a chronic problem: difficulty sourcing suitable land for infrastructure.

India plans to boost clean power capacity to 500 gigawatts by 2030 from just 165 GW in April. It also wants to reduce carbon-emissions intensity by more than 45% below 2005 levels by then, and become carbon neutral by 2070. Japan seeks to cut carbon emissions by 46% from 2013 levels by 2030 and become carbon neutral by 2050. It aims for 36% to 38% of energy to come from renewables by 2030.

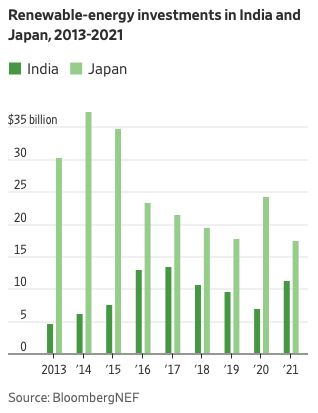

Green investment in India has come roaring back after a mid-pandemic slump but will have to accelerate much more to make it into the neighborhood of those goals. According to BloombergNEF, India will need $223 billion over the next eight years just to meet its solar and wind capacity targets, versus $83.2 billion invested in clean energy from 2013 to 2021.

In comparison, Japan attracted $226.1 billion during the same period and may need at least ¥150 trillion ($1.102 trillion) in combined private and public investment in the next decade to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050, according to official estimates.

India has established itself as one of the largest renewable-energy markets in the world, and its rising power demand and government support for green power have made it the most attractive investment destination for renewables among emerging markets, according to a 2021 report by Climatescope.

But India shouldn’t take that momentum for granted. Rising interest rates and inflation may lower returns on new projects. And challenges around land acquisition and power-purchase-agreement renegotiations may also threaten future investment, according to BloombergNEF.

Japan may not face such strong financial headwinds, since the central bank has so far held fast to its loose monetary stance. But the country’s renewable projects continue to struggle with a scarcity of land. Due to a lack of suitable sites, many projects in Japan are built in hilly areas where developers spend a lot but aren’t able to achieve economies of scale, according to Isshu Kikuma, a Japan analyst at BloombergNEF.

Japan’s shift from a feed-in-tariff renewable-power pricing model to a feed-in premium, a policy more aligned with market forces, is also likely to increase investment risk and operational requirements. The older policy offered a high, fixed power-purchase price for all renewable plants. That, along with a long-term purchasing contract gave security and bankability to renewable projects, according to Minh K Le, Head of Hydrogen Research at Rystad Energy.

Like China, India and Japan will be key players in Asia’s transition to a more climate-friendly energy and economic model. The challenges they face are also nearly as large.